Viking Sword Type H/I – The Workhorse of c. 800–950

The Viking Sword Most Warriors Actually Carried

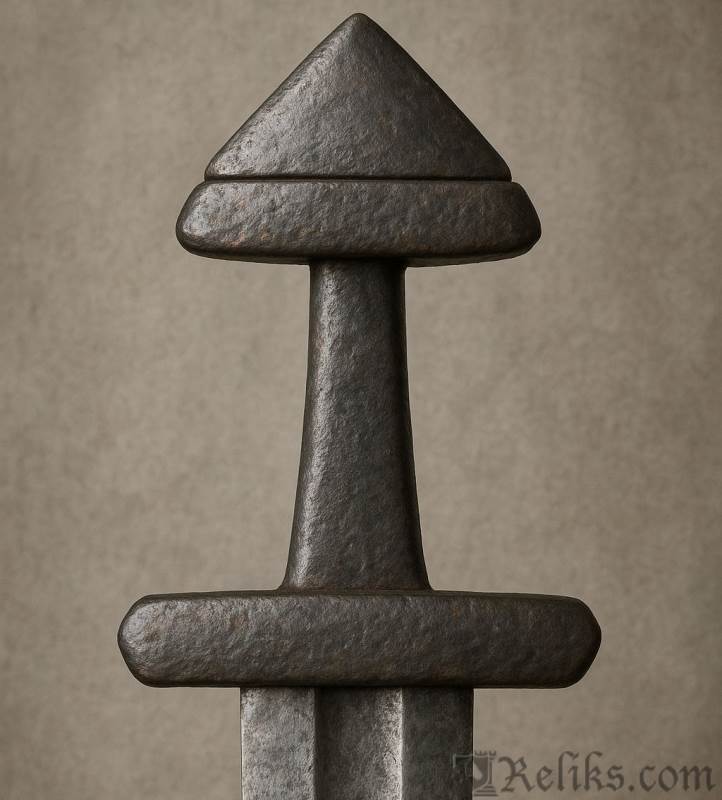

Among all Viking sword types, Type H is the most common and longest-lived. It appears right at the dawn of the Viking Age, thrives through the first half of the 9th century, and continues—evolving—well into the 10th. If you picture a “typical” Viking sword with broad guards dressed in silver/bronze strips and a three-part pommel, you’re probably imagining Type H.

Archaeological Description (Type H)

Viking Sword Type H – The Workhorse

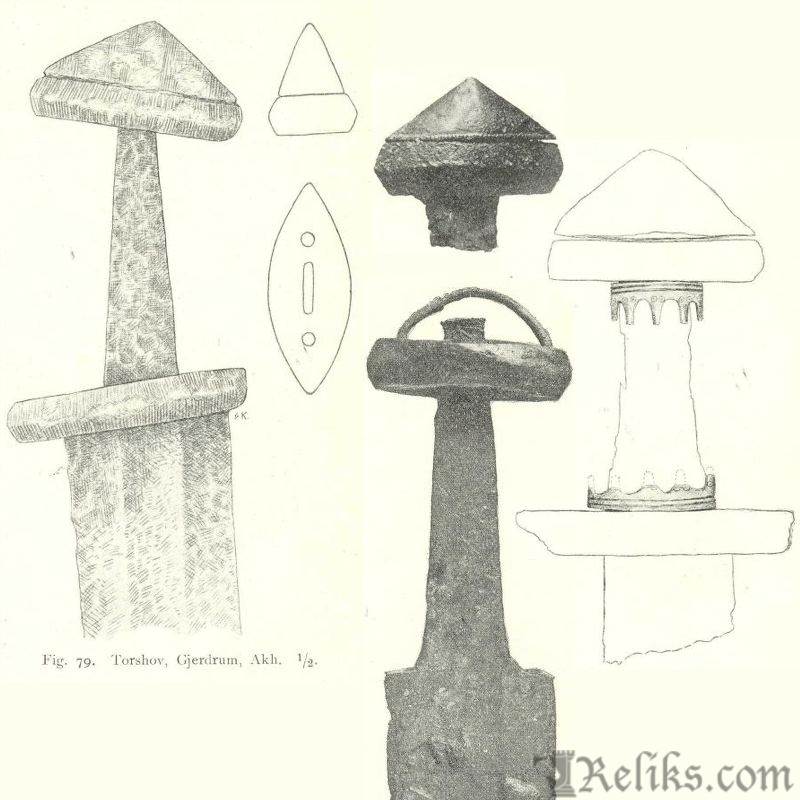

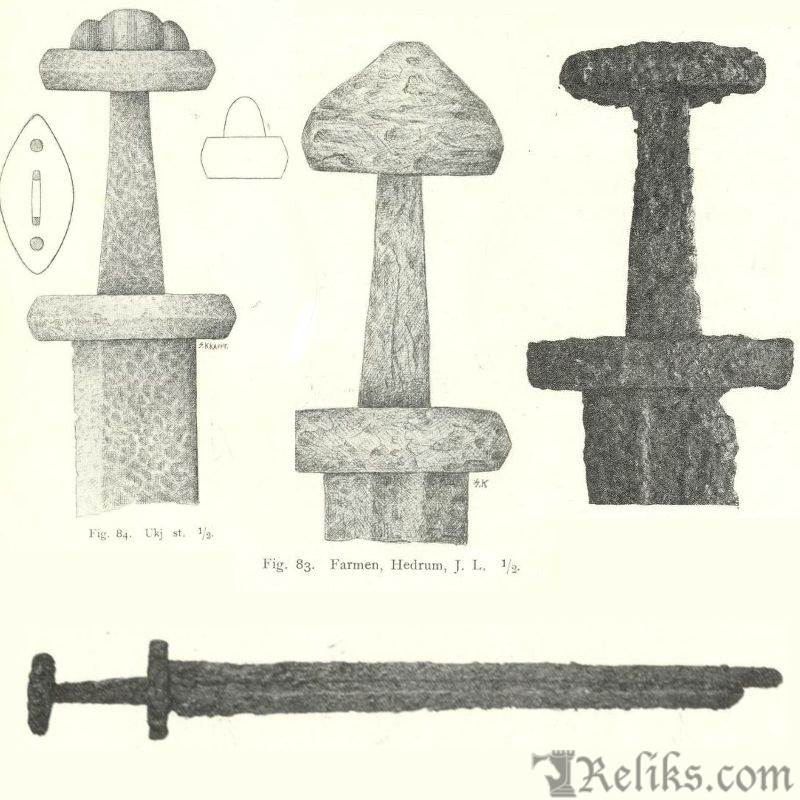

The defining feature of Type H swords lies in their guards and pommels. The guards are broad and elliptic in cross-section, with the upper guard often extremely wide—sometimes reaching up to about 3.6 cm. Earlier examples tend to have ridged or arched sides that give them a heavier, more massive appearance, while later ones appear flatter and more restrained in form. The pommel is a characteristic three-part, tri-lobed piece with a wide base and a height typically ranging from about 2.5 to 4.2 cm. In many finds, the pommel itself is missing, yet the distinctive broad upper guard, often decorated with bands, still makes identification straightforward. Unlike the earliest A, B, and C types, where the pommel or upper guard could simply be peened onto the tang, Type H hilts usually had the pommel riveted firmly to the upper guard.

Decoration is one of the hallmarks of this type. Swordsmiths employed a signature strip-inlay technique, cutting tight horizontal grooves into the iron and hammering in thin plates of silver, copper, bronze, or occasionally brass, which gave a golden appearance. The patterns varied from simple alternating vertical bands to checkerboard or rhomb motifs, and sometimes stepped, ladder-like (“trappeformet”) designs. Today, many of these surfaces appear ribbed because of corrosion and wear, but originally they would have looked smooth and finely polished. Some swords also feature beaded bronze bands, known as vettrim, set between the pommel and guard, while others display plain plates on the faces of the guards. Rarely, entire guards were cast in bronze, and in exceptional cases even the pommel itself was bronze-covered.

The blades that accompany these hilts show notable variety. Both double-edged and single-edged examples occur; of the nearly two hundred classified blades, roughly three-quarters are double-edged while just over a quarter are single-edged. Many show evidence of pattern-welding, and a number carry inscriptions, with some authentic ULFBERHT imports and others likely local imitations.

Within the broader type, archaeologists have also observed a few unusual constructions. Some swords merge the upper guard and pommel into a single piece, reflecting a structural trend that had already appeared when Type B gave way to Type C. Repairs and replacements sometimes led to hybrid forms—such as a C-type upper guard fitted over an H-type lower guard, or an H hilt that was topped not with a true pommel but with a bronze loop acting as a makeshift substitute. In rare cases, animal-head collars appear between the guard and pommel, recalling ornamental traditions found on the earlier D and C types.

Relationships & the Road to Type I

- Beginnings: H emerges from the heavy, prestige-leaning early forms (B–E). Early H swords still look massive and “local” (ridged, thick guards).

- Evolution: Over time, ridges flatten, band-work simplifies, and proportions get a touch slimmer.

- Transition to I: When the guards lose the older ridged profile and take on a clean, flat look—while retaining the band-inlay vocabulary—we’re essentially in Type I territory. In typological terms, I is a younger, streamlined branch of H.

Historical & Cultural Context

Petersen Sketches (fig.79-82)

Type H swords emerge right at the dawn of the Viking Age, when Scandinavian raiders were beginning to cross the seas in earnest. This was the period of the earliest recorded raids on England, Ireland, and Francia in the late 8th and early 9th centuries, when the longship transformed Norse society into one that looked outward with both hunger and opportunity. At home, chieftains consolidated their power, trading networks stretched from the North Sea to the Baltic, and new burial customs reflected a warrior elite that carried prestige weapons to the grave. Against this backdrop, the Type H became the default sword of the age—a symbol of status and battlefield identity from the early 9th century through the middle of the 10th. It was especially common along the coasts and in Trøndelag, a region that remained a stronghold of Viking culture well into the mid-900s, even as newer types began to appear.

The archaeological record confirms this long span of use. Early associations place Type H alongside axes of the A–D types (especially D), spearheads of the A, B, and E types, shield bosses such as R 564, early rattle amulets, and occasional oval brooches—all finds that firmly anchor it in the opening phase of the Viking Age. Later graves tell a story of continuity and adaptation: Type H swords appear with younger axes (E, K, and L), later spearheads (F and I), lower-profile shield bosses like R 562, and rattles of younger form. Together, these combinations show that the H-type persisted well into c. 900–950, bridging the shift toward newer hilt forms such as the I-type.

Another layer of meaning comes through imports and identity. While Ulfberht and other imported blades made their way into Scandinavia—often treasured as high-status weapons—the hilt style of Type H remained distinctly Scandinavian. The richly inlaid silver, bronze, and copper bands that decorate so many of these hilts gave them an unmistakable look, marking their owner not just as a warrior but as a participant in a shared cultural expression. These swords embodied the duality of the Viking Age itself: outward-looking through trade and raiding, yet rooted in a distinct northern tradition of craft and symbolism.

Distribution and Finds

Petersen Sketches (fig.83-85)

Petersen recorded 213 Norwegian H-type hilts—by far the most of any type—with a quarter from Trøndelag alone. Coastal regions are rich; Akershus/Hedmark and some inland districts are comparatively sparse.

Beyond Norway, Type H is widespread: Sweden (Birka/Björkö, Gotland, Uppland, Gästrikland, Jämtland), Finland and further east (incl. Russia), the British Isles (Dublin, Orkney/Rousay, Edinburgh collections). Denmark: comparatively rare in museum tallies.

Dating Summary

Origins: Just before/at the start of the Viking Age (late 8th into early 9th).

- Peak: First half of the 9th century (coeval with heavy C/D/E).

- Longevity: Second half of 9th ? mid-10th century in some regions (younger associations; narrower fullers on some late blades).

- Bridge to I: The younger, flatter H-style hilts and band patterns segue into Type I (c. 9th–10th century).

For Collectors and Enthusiasts

Type H is the quintessential Viking hilt: broad band-inlaid guards, three-part pommel, and a profile that reads “Viking” at a glance. It’s also the most accessible in museums and publications—perfect for enthusiasts who want a representative piece of the period. Because it spans so long, you’ll find early, heavy/ridged H and later, flatter H (slipping toward I)—a great teaching case for evolution across the 800–950 window.

Closing Reflection

Type H isn’t just common—it’s foundational. It reflects how Viking smiths standardized a Scandinavian visual language: iron hilts dressed in contrasting metal bands, robust proportions, and a practical three-part pommel. From this backbone, Type I streamlines the look as the 10th century matures. Think of H as the classic, and I as its sleeker, later iteration.

Core classification based on Jan Petersen, De Norske Vikingesverd (1919). Additional commentary by Reliks.com.