Viking Sword Type K – The Five-Part Pommel and a Frankish Connection

Prestige Meets Standardization

Type K marks one of the most recognizable turning points in Viking sword design. This is the moment when the five-part pommel—the so-called quinquepartite form—really takes hold. The effect is striking: a crown of five lobes standing proud at the hilt, often with the central lobe slightly higher than the rest. It was a look that signaled prestige, but also hinted at a new age of standardized forms that could be repeated and adapted across workshops. In Norway, Type K appears early in the 9th century, lingers well into its later decades, and even seeds younger offshoots such as the O-type.

Archaeological Description

Viking Sword Type K – Five-Part Pommel and Carolingian Roots

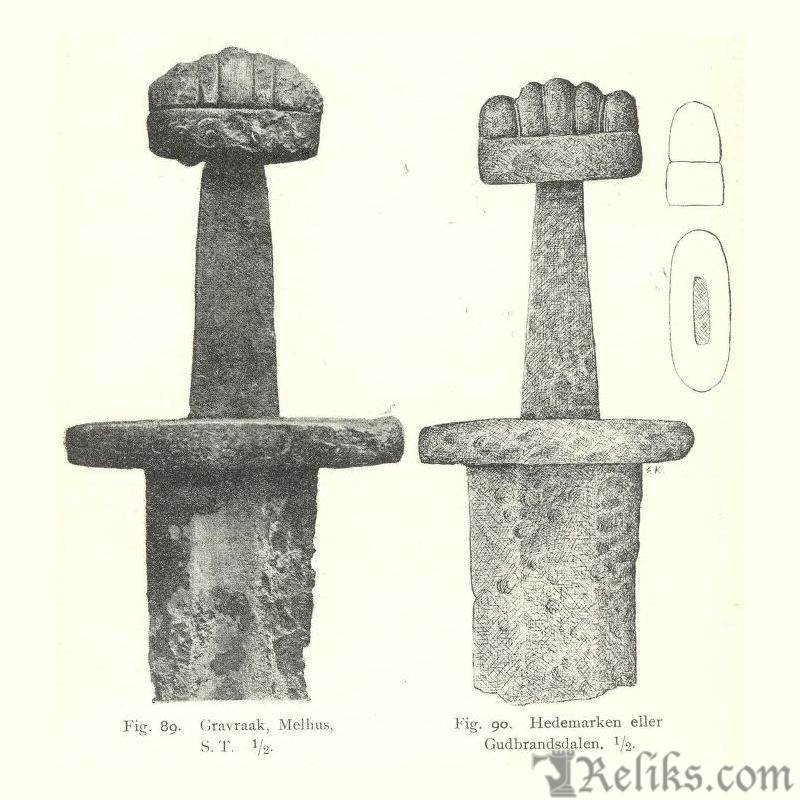

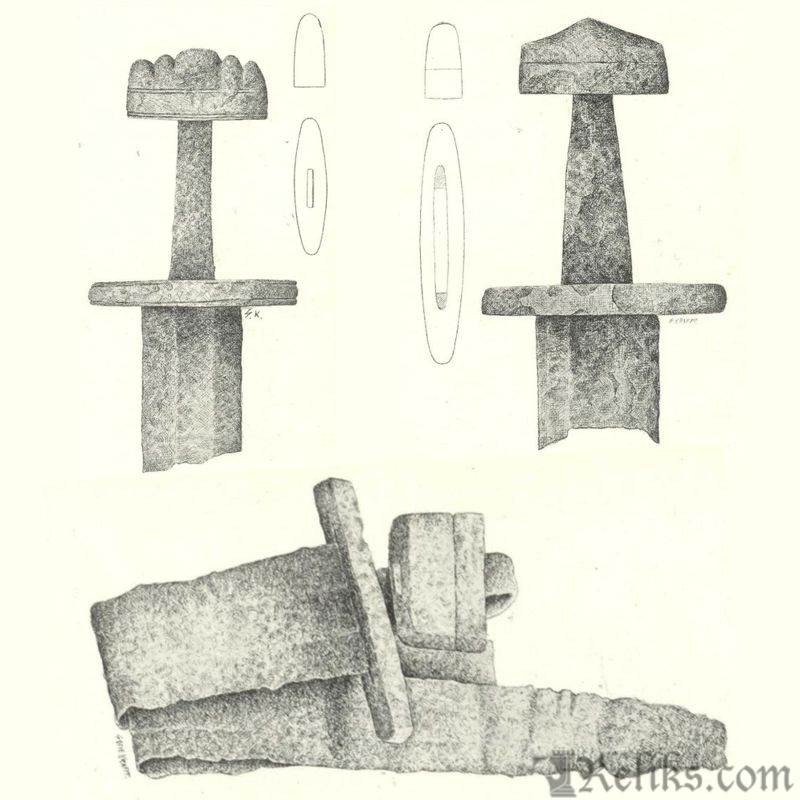

The classic Type K hilt consists of straight guards with rounded ends and a rectangular to gently curved cross-section—quite different from the pointed-oval sections of the I-type. Above this rests the iconic pommel. In its fullest form, five distinct lobes stand in a row, separated clearly enough that the design cannot be mistaken. Most examples are built in two pieces, with the pommel riveted separately onto the upper guard. Yet smiths sometimes experimented: a few K-swords show a “merged” construction where the pommel and guard were forged as a single block, with incised lines carved to mimic the divisions. In still plainer versions, the lobes collapse into a single rounded crest, only faintly recalling their five-part ancestry.

Decoration is usually achieved with the familiar Viking strip-inlay technique. Thin bands of silver, occasionally bronze or brass, were hammered into tight horizontal grooves. The results could be simple parallel lines or stepped, ladder-like motifs, and sometimes twisted wire was pressed into the grooves between the pommel lobes. The blades are almost always double-edged, with some showing fine pattern-welding. A handful are of such quality that they may have been imported from Frankish workshops, or at least made in imitation of them.

Relationships to Other Types

Type K shares a family resemblance with H in its inlaid decoration, but the five-part pommel sets it apart instantly. The occasional “one-block” variants echo an older story: just as B evolved into C through merging, K could collapse into simplified one-piece hilts. From these reductions, Petersen argued, the O-type almost certainly arose. Thus K stands as both a culmination of continental influence and a seed for future Scandinavian simplifications.

Historical & Cultural Context

Petersen Sketches (fig.89-90)

The roots of Type K lie not in Scandinavia but along the Rhine and in the Carolingian sphere. In the 8th century, Frankish smiths developed this crowned pommel style, and by the first half of the 9th century, Viking raiders, traders, or mercenaries had carried it north. Once in Norway, the form spread widely and quickly took on a local life. Some swords retained all the rich band-inlay of their continental cousins, while others stripped down the decoration and simplified the build.

The contexts where K-swords appear tell us much about their use. They are found with spearheads of B, C, and F types, axes of the D and E families, and shield bosses such as R 564. These combinations root K firmly in the early Viking Age, though finds with F-type spears show that the type continued in use into the later 9th century. This was the age when Viking armies were striking deeper into Europe, and the K-sword—with its mix of imported prestige and adaptable local variants—fits neatly into that story.

Distribution and Finds

Petersen listed thirteen reliable K examples from across Norway. They cluster in Hedmark and Oppland in the east, but also appear in Agder, Telemark, Sogn & Fjordane, Romsdal, and Trøndelag. Most are the classic two-piece hilts, though three are merged or one-block forms (such as the finds from Kilde in Åmot, Magera in Åkre, and Neding in Holme). Beyond Norway, the five-part pommel is well known: France, the Rhineland, Schleswig, Livonia, and even Ireland have produced parallels. These confirm that the type traveled west to north as part of a shared martial culture.

Dating

Type K emerges on the continent in the 8th century and is present in Norway from the early 9th onward. The earliest Norwegian examples often occur with older axe and spear forms, suggesting adoption around the opening of the century. Later finds paired with F-type spears show it persisted through the mid- and late 9th century. Rather than pigeonhole it as a “late 9th” sword, the evidence suggests K spans the whole century, evolving and simplifying along the way.

Special Variants

Petersen Sketches (fig.91-93)

Several unusual finds help trace this evolution. A sword from Finstad in Løten has a smoother, two-piece pommel outline but still echoes the five-lobe design. Another from Store-Finstad reduced the pommel to a plain square block—an extreme simplification of the K form. At Kleppen in Vågå, a single-edged blade carries a one-piece arched crest, while at N. Hen in Ådalen a very small one-piece version seems to hover between K and later X-types. These outliers show how smiths experimented with cost, speed, and local taste while still referencing the prestige model.

For Collectors and Enthusiasts

For today’s collector, Type K is one of the most rewarding Viking hilts to study. The five-part pommel is visually distinctive, immediately recognizable, and steeped in continental connections. Replicas often highlight the silver-inlaid bands and the option of twisted wire between the lobes, details that distinguish genuine K-style ornament. For reenactors and educators, the type tells a powerful story: how Viking smiths borrowed from the Carolingian world and transformed foreign prestige into a weapon that became unmistakably their own.

Closing Reflection

Type K swords sit at the crossroads of Viking and Carolingian craftsmanship. Born in the Frankish heartlands, they were carried north and embraced by Scandinavian smiths, who both celebrated their prestige and pared them down into simpler forms. From these experiments emerged the O-type and beyond, making K a keystone for understanding the swordscape of the 9th century. In many ways, it is the perfect Viking story: a blend of import and innovation, prestige and practicality, crown and blade.

Core classification based on Jan Petersen, De Norske Vikingesverd (1919). Additional commentary by Reliks.com.